Essays on Dissociation and Depersonalisation

Essays on Dissociation and Depersonalisation

Living in a Dream: A collection of essays on dissociation and depersonalisation

By Matt Gwyther, Gwynnevere Suter, Sarah Coyle, Joe Perkins & Gwendalyn Webb

In collaboration with Unreal Charity

Introduction

by Matt Gwyther

** Content warnings: this collection of essays discusses dissociation, derealisation, depersonalisation, suicidal ideation, grief, trauma, isolation, amnesia, identity confusion, identity alteration, psychosis, self-esteem, depression, anxiety

My journey into the world of dissociation and depersonalisation began some time ago, but it was reignited when I started working on an international research project led by Dr. Jane Aspell called 'Living in a Dream: Body and Self-Experience during Waking and Dream States in Depersonalisation.' Although our research focuses on depersonalisation traits in a non-clinical group, I also researched depersonalisation in its clinical form: Depersonalisation-Derealisation Disorder (DDD [sometimes referred to as DPDR]). Depersonalisation describes the feeling of disconnection from one's own body and self, and derealisation describes a disconnection from the world. I was struck by the accounts of individuals struggling with DDD, and how much of an impact it had on their day-to-day lives. It was difficult for them to communicate their experience to others. Depersonalisation is intimately linked to selfhood: the feeling of being a subject in the world. Given the profound disturbances to the sense of self in depersonalisation, examining it more closely can provide valuable insight into perennial questions around the self, such as what the self is, where it is, and how it is generated.

The public's knowledge of DDD and other forms of dissociation* is relatively limited, despite it being a common condition. In fact, it occurred to me that a distinct and out-of-place experience I had several years ago might have been a transient spell of depersonalisation or another form of dissociation. As I spoke with collaborators on the project, it became clear that several of us had a story to tell about our own experiences with forms of dissociation and depersonalisation.

While there is some great work in the academic literature on this topic, I felt that the richness of experience and the human angle was often diluted. It seemed to me that some kind of bridge would be useful, a way to integrate accounts of first-hand experience with reflections on literature and theory. So myself and two other collaborators on the project, Gwynnevere and Sarah, set out to create a collection of first-hand accounts and thought pieces.

Later on, I contacted the Unreal charity, which raises awareness and provides support for those struggling with DDD. From this, I had an exchange with Joe Perkins, trustee and board member at Unreal, who provided a wonderful written contribution. I had read Joe's excellent book 'Life on Autopilot,' which I highly recommend for anyone looking to understand more about the lived experience of DDD. Joe kindly put us in touch with Gwendalyn, also a board member at Unreal, who contributed a wonderfully written, albeit harrowing**, account of living with DDD.

Working with the contributors, we found that we were similarly aligned in wanting to raise awareness of these experiences and to encourage people to be honest and open about their lived experiences. In the spirit of encouraging people to explore their experience in a more creative mode and without any restrictions around content or tone, we ended up with a superbly eclectic mix of styles and angles. I also incorporated some AI-generated artwork to accompany the collection. Despite how quirky the collection is in its mix of contributions, some common themes emerged: individuals attempting to understand their own experiences, the difficulty of communicating these types of experiences to others, and the lack of awareness about them.

Our hope for this collection is that it will bring people some solace and raise awareness of DDD and other forms of dissociation.

*although the collection discusses depersonalisation and dissociation we do not go into detail about the latest thinking on clinical classifications – for more on this see recent papers from L. S. Merritt Millman and colleagues (here or here)

** Content warnings: this collection of essays discusses dissociation, derealisation, depersonalisation, suicidal ideation, grief, trauma, isolation, amnesia, identity confusion, identity alteration, psychosis, self-esteem, depression, anxiety

Part I — Dissociation and the Self

By Gwynnevere Suter

How dissociation changed my view of self and what it means to be.

Part I: Introduction

**How dissociation changed my view of self and what it means to be.

**By Gwynnevere Suter

Dissociation is a commonly experienced but underdiagnosed psychiatric symptom causing people to feel disconnected from their body and the surrounding world. However, it can have implications beyond just the experience of one’s world and body. Gwynnevere recounts how dissociation impacted her perception of self and what it means to be an identity.

Content warning, this piece discusses: dissociation, derealisation, depersonalisation, amnesia, identity confusion, identity alteration, psychosis, self-esteem, depression, anxiety.

Key words: Dissociation, derealisation, depersonalisation, sense of self, bodily self, conceptual self, experiential self, lived experience

Into the Void — My First Experience

I first dissociated Sunday August 4th 2019. I remember this precisely because, unlike most dissociative experiences, this wasn’t a faint smudging of the world, a subtle separation between me and reality. Instead, I woke up to what I knew was a completely normal day, but one that felt indescribably broken.

When I spoke, I would be surprised by the sound I heard, let alone that it conveyed what I was thinking. When I interacted with someone, it felt as if I was alone in the universe, vainly sending out a signal that some distant being might one day receive. Most perturbingly, whenever I tried thinking about my thoughts and sentience (a process called metacognition), it would feel as if I had only then become conscious, as if during any moment when I was not actively thinking about my existence (or possible lack-thereof), I ceased to be real, or at least awake.

Everything was exactly as it should be, yet nothing seemed right.

At the time, I was woefully unequipped to understand what was going on. Looking back at chat logs with my friends, all I could say to describe my experience was “I was just way too into my head”. I did have one idea, however, though it proved to be neither helpful nor correct. I had recently finished reading the book The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise by the 1960s Scottish psychiatrist RD Laing1. In the book, Laing explores human experience and interactions through a phenomenological lens, arguing, for example, that we can never truly tap into each other’s experiences, but instead only interpret our experience of someone’s experience. He then goes on to integrate this with his observations about psychotic experiences and schizophrenia. The book is provocative, immensely thought-provoking, and a very worth-while read. However, it discusses psychosis with an understanding from the 1960s which seems to consider dissociation a part of psychosis. Thus, after my day of unreality, I was thoroughly convinced I was in what Laing called a “post-psychotic” state (curious considering I had never experienced any symptoms of psychosis). Thankfully, I eventually learnt what dissociation was, and no longer had the looming fear that RD Laing and his psychosis-induced “hypersanity”1 was just around the corner.

And Down the Lane — An Introduction to Dissociation

Before delving into my experiences with dissociation and the impacts it had, I think a brief introduction into what dissociation is and feels like is in order.

Dissociation is a psychiatric symptom found in various mental health and personality disorders. It is a core symptom for dissociative disorders such as Depersonalisation/Derealisation disorder, Dissociative amnesia including Dissociative fugue, and Dissociative Identity disorder (previously known as Multiple Personality Disorder), and is sometimes found in other disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder or schizophrenia 2-3. However, dissociation can also occur outside of a pathological context, typically during very stressful or surreal moments. Surveys suggest 1.2-1.7% of the British population at any one time will be experiencing dissociation, with a lifetime prevalence of 26-71% 4. Therefore, it’s very likely you the reader have either dissociated at some point yourself, or at least know somebody who has.

There are multiple components of dissociation. These are commonly modelled as five aspects: Derealisation, depersonalisation, amnesia, identity confusion, and identity alteration 5. The last three aspects are not as commonly experienced as the first two. In fact, as I have never experienced proper identity confusion and alteration, wherein you may be unsure of who you are or find yourself behaving in unusual ways and using names you do not usually use 5 I will not write on it further. Similarly, I am not aware of having any significant dissociative amnesia (only some difficulty remembering details of things that happened when I was dissociated), so I will leave more experienced writers to that. Instead, I wish to focus on depersonalisation and derealisation, which I know intimately and which many more readers will come across in their lives.

Depersonalisation is the disconnect between one’s bodily sensations and the experience of them. A depersonalised person may feel that they are not truly in their body, nor that anything their body does is caused by them (even if the action agrees with what the person wants to do – I have had multiple occasions where I’ll be speaking or going somewhere and wonder however did my body know that was what I wanted to do). This is not the same as an out-of-body experience (OBE). During an OBE, the individual will actually see their body from a different perspective 6 whereas when depersonalised, the individual will still see everything from first-person perspective, even if it feels like they are separate. Further, they may feel like they are just passively watching themselves (like a movie) and may not feel physical or emotional sensations as strongly or at all. For example, I might be feeling thirst, but just not recognise that the thirst I am feeling is my own. Alternatively, I may identify with the sensations I feel, but they will be faded or fuzzy (similar to a warm blanket swaddling your mind). Lastly, depersonalisation can cause difficulty paying attention or keeping track of time 2. This often manifests as zoning out a lot or being unable to finish a thought because you keep forgetting what you were trying to think about. Of course, not all dissociation is this intense, and often depersonalisation can feel like just a tiny lag or dampening between your body and your experience.

While depersonalisation is the dissociation between your body and mind, derealisation is between your mind and the world. True to its name, derealisation can make you feel as if the world around you is not real. Very important to note, derealisation is not psychosis, wherein you may have trouble identifying reality. There are no hallucinations or delusions associated with derealisation 2. When I am derealised, I am always aware that the world around me is real, the distinction lies in the fact that it just doesn’t feel like it. Instead, the world seems flat, almost as if I am watching it from a screen. I still maintain my sense of agency and body ownership, though it can feel as if my actions have no consequence because the world I am interacting in is not the world that will continue to exist. A good analogy to this is to imagine you are playing a video game and you want to try something out for fun but have it not be part of your main playthrough, so you create a save-file and try your idea from there so that you can later return to that point and continue as normal. While playing in that moment, you exist in a sort of limbo, wherein the game’s reality is unchanged and will react as normal, but you the player experience it differently. This is similar to what it feels like to exist in a derealised reality. You are consciously aware that everything around you is real and will continue to be so, but to you in that moment it feels disconnected and trivial. It’s akin to when you repeat a word over and over again until it just sounds odd. You know the word is still the same word with the same meaning, but each time you repeat it, you can’t help but think more and more about how it’s just a random meaningless collection of sounds. Again, being derealised is not always this extreme and can often just manifest as a slight flattening of reality, where everything seems just that tiny bit more dream-like than usual.

Despite modelling depersonalisation and derealisation as different phenomena, in practice they are often experienced together and are indistinguishable. Though it is true that you can experience one more than the other (for example, I tend to derealise more often), it is unlikely that someone will only ever feel one form of dissociation. Indeed, just looking at my account of the first time I dissociated, you can see clear elements of depersonalisation and derealisation together. My surprise at actually speaking points to depersonalisation. Meanwhile, my perceived isolation and inability to conceive of others being present is classic (albeit very intense) derealisation. My sudden awareness during metacognitive thought is a little less clearly one or the other. You might attribute cognitive fuzziness to depersonalisation, but a sense of unreality to derealisation. Moreover, you can tie all of these experiences together by the lack of control the individual has over what is happening to them. Though, dissociation has many similarities to other common phenomena like some meditation, flow states, or exhaustion, it is crucially different in that the individual is not able to control their mental state and become more alert and present (a process called grounding). There are specific grounding techniques that can be helpful, but even then, an element of dissociation often remains.

I am aware that understanding the experience of dissociation can be a bit of an ‘if you get it, you get it’ situation. Therefore, here are a couple metaphors and tricks that others have found useful. To start with, I want you to remember your last long journey. It can be a commute, a long train-ride to visit a friend, or anything. Throughout this journey, can you recall every moment? Every detail of what you were doing, listening to, who was around you? Perhaps you can, and in which case I applaud you because my memory is not that good. More likely, you can recall a couple things, such as a funny ad you saw or a loud baby crying, but a lot of it is completely gone. This phenomenon of zoning out during something very familiar is not synonymous with, but very similar to the outcome of dissociation. You are aware the time has passed and know what must have happened (usually), but the specific details elude you as you spent so much of it on auto-pilot. A similar thing occurs when listening to a song you know well and you swear the moment you turned it on, it was already over, though you cannot recall the whole thing playing. As a final aside, I want to give one little demonstration.

In a moment, try closing your eyes and picturing your favourite holiday. Try to recall how everything looked, who was there with you, what you could hear, smell, feel, even taste. Close your eyes now and try this before reading on.

Now, having done all that, can you describe what you saw at that moment? Not what you were picturing, but what your closed eyes were perceiving (probably just darkness and some faint swirling lights). This can be a little like how very strong dissociation feels. You’re passively perceiving things from the world, and if something very sudden happened such as a bright flash of light, you would be aware, but otherwise you simply do not think to attend to it. This is not a perfect comparison, and can only account for the outcomes of dissociation, nor any of the disconnect with the body or world, but it captures something of the general experience.

I Might Have Been Lost — Integrating My Senses of Self

Now that you have an appreciation of what it means to be dissociated, it is time to explore how such an experience managed to affect my concept of self in two key ways, and what this meant for other aspects of my life. Throughout this, I do not wish to catastrophise nor romanticise dissociation. My experiences with it have been ambivalent: sometimes it was annoying and scary and got in the way, other times it has been a helpful coping-mechanism and even catalysed significant personal growth. It is important to acknowledge both sides of dissociation, and that these can vary immensely between people. If you would like to seek support for your dissociation or just find out more, there are some links here which I hope can be of help.

The first shift in my perception of self that I noticed was, perhaps unsurprisingly, my connection to my body. There are numerous studies indicating that dissociation is associated with a poorer interpretation of bodily signals 6-7, and indeed in depersonalisation we see a clear separation between the body and conscious mind’s perception. Despite all this, I felt more connected and present in my body than ever before. This wasn’t an anti-depersonalisation trick; I could still depersonalise and feel a lack of control and connection to my body’s actions and experiences. Rather, the tie between my conscious mind and my body felt more concrete. Even if we felt separate sometimes, I was more aware that my body was still my own and I was located within it. Upon reflection, I believe this happened because of my derealisation. As I was spending so long psychologically isolated (I knew I was communicating with people, but my experience was that of speaking into The Void), I was forced to really be connected with myself and acknowledge my own presence. Ironically, feeling alone with myself, surrounded by unreality, was the perfect way to identify my existence. I was sure I existed as I had thoughts, and consciousness, and perception, yet everything else was so distant. It was this contrast that made me aware of how deeply rooted in my body I was. It didn’t matter that sometimes things didn’t feel as intensely as they should, or that my actions would occur in accordance with what I wanted, just unbidden. I was my body as much as I was my consciousness. This can be summarised in a text I later sent my friends on the matter: “Rather than feeling like I have a barrier between my thoughts and the world which is my body, it’s just like me plopped in the world interacting directly.”

The second shift may appear rather in contrast to the first, though, fundamentally they originate from the same integration of body and mind (take that Descartes). It differs in that, unlike the above change in my embodied self, this was a shift in the perception of my more conceptual and cognitive self. Further, this initially seemed like an overall loss or discarding of a self-concept, rather than a deep integration. Essentially, I realised I no longer had an opinion of myself. What’s more, it wasn’t that I had forgotten how to have one, it simply didn’t seem relevant or actually possible anymore. I was still aware of my personality, how I behaved, my opinions and values. I could describe myself to others, detail and predict how others would react to me. I even maintained opinions on certain behaviours and traits I had. However, none of this culminated in an overall opinion of myself or elicited any feeling (be it love or hate) towards myself. It just no longer made sense to me to have an opinion. If I was myself, how could I have an opinion on my self? There was still use in caring about specific things like how well I listened to others, how much I liked singing, whether purple hair suited me. But to form a judgement on me as a collective of all of these things? It didn’t seem relevant. My self had become so deeply linked to my experience, that any attempt to extract and decontextualise it seemed contrived and invalid. In a way, I had managed to achieve self-neutrality, though entirely inadvertently. While, this might appear in antithesis to the aforementioned merging of mind and body, I believe the same process is exactly what happened here. My conceptual self became integrated into my experiential and bodily self so much that they ultimately became synonymous.

Armed with this united self and recent awareness of it, I began to notice the wider reaching effects it had on my thoughts and mental health. The first thing I realised was that I had finally achieved what so many school talks, mental health campaigns, and conversations with others had been advocating for: I became my own best friend. Not in that I didn’t have other close friends (in fact I had an excellent friend group and support network), but rather I realised there was no reason I couldn’t be friends with myself as well. There was no one in the world with whom I had more similar opinions or interests, no one who could appreciate my perspective more, no one with whom I could spend more time (something particularly valuable given my proclivity for derealisation). Again, this didn’t mean I had no interest in others, simply that when I was by myself, there was no real reason I couldn’t enjoy it. At the same time, I had the related realisation that there was nothing stopping me from at least trying to be happy. Though to many this may seem obvious, for somebody with a history of depression and anxiety, to truly believe and understand the implications of it was indescribably significant. I believe that this is possible through other routes. However, in my case, it seems the direct result of unifying my conceptual and experiential selves to allow the disregard of the self-narratives that had previously inhibited such beliefs.

However, although my dissociation triggered the integration of my conceptual, experiential, and bodily selves, it also managed to create a novel distinction. This was first seen during my first dissociative episode. During that, I felt a qualitative difference between my normal thinking consciousness and my self-reflective one. If you recall, whenever I would become aware of my awareness, I would feel a sudden new awakeness, as if everything before then had not been truly perceived. These are not distinct senses of selves in the way the conceptual, experiential, and bodily have been modelled, nor are they strictly the result of dissociation. I remember (with amazement now) how when I was younger, before I ever dissociated, I would enjoy sudden bursts of metacognition and existentiality. The difference now is that these modes of cognition are accompanied by such different thoughts and moods that they are two different experiences.

But I Found My Way — Where I Am Now and Closing Remarks

At this point, nearly three years later, things are rather different. Namely, my dissociation has become much milder. This is in part because it genuinely happens less frequently and intensely, but also because of learning what triggers it and how best to ground myself. This means that a lot of the pressures that shaped my thinking earlier are no longer there, and so the effects have begun to fade. While I can still appreciate the thinking and perspectives I described above, the intense self-identification and resulting neutrality no longer fit as much. It still feels odd to attribute any particular opinion or emotion towards myself overall, but more it’s more like I choose not to, rather than not understanding how. I have made an active effort to maintain some beliefs like being your own best friend and choosing to be happy, but others have simply faded with time.

In a way, this hearkens back to a core argument in Laing’s The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise. Laing frequently described his patient’s psychotic episodes as a “voyage of discovery” 1, arguing that through this “voyage” the patient could gain new insights into the world and themselves. While I wouldn’t quite describe my three years of on-and-off dissociation as a voyage which “heal[ed my] own appalling state of alienation called normality” 1, its impacts on my perspective on what it means to be an identity and be real cannot be ignored. Again, unlike Laing, I am hesitant to paint my experiences as a phenomenal discovery. However, that does not mean I cannot appreciate the healing they brought me.

Most likely, there’s no grand conclusion to be drawn on the merits or struggles of dissociation, nor on how best to conceive of yourself. Instead, I will leave you with one piece of advice: don’t try to interpret your mental health only through controversial psychiatrists from the 1960s; as insightful and intriguing as they are, the contributions of a few more modern texts might go a long way.

Part II — Bringing Back a Glimpse of Unreality

By Matt Gwyther

A brief episode of depersonalisation, the trouble with understanding altered states of mind and a new form of AI-assisted psychotherapy.

Part II: Introduction

A brief episode of depersonalisation, the trouble with understanding altered states of mind and a new form of AI-assisted psychotherapy.

By Matt Gwyther

This piece is composed of three sections. In the first, I describe a period of depersonalization, including the causes, how it felt, and its impact on my life. After reflecting on the difficulty of describing this period, the second section discusses the general difficulty of understanding altered states of mind. Finally, the third section discusses some experimental ideas for getting closer to altered states of mind, such as AI-enhanced psychotherapy.

A Brief Episode of Depersonalisation

Living through a period of absence

In 2011, I experienced a transitory form of dissociation which I attribute to stress, ill-health, and several courses of prescription steroids (a note on prescription steroids) used to treat inflammation.

For a month or so, I experienced ‘absence’ in a way not previously felt. This absence can perhaps be best described as feeling as though ‘I was not fully there’. So fundamental was this absence that when I look back at photos from this period, I look distant. My memory of the period is hazy and vague at best, like a peculiar and uncanny dream. It felt as though I formed very few memories of events. To this day, the moments I recall are mostly only accessible when looking at photos. Everything felt a step removed from my usual experience. Conversations were much more difficult and peculiar. In groups I tended to ‘zone out’, often feeling as though I was not there or, in some basic form, just witnessing people and events around me. It was certainly a very ‘numb’ period with an absence of feeling, a kind of emptiness or flatness of my emotional landscape. Beyond the greyness of anhedonia in depression, it wasn’t just that I couldn’t experience pleasure, it was more like I couldn’t experience anything. Here there’s a strange paradox, I did of course have experience in the basic sense of living through life experiences, but the ‘I’ necessary for experiencing those experiences was fundamentally changed.

Another marked phenomenon was that I felt distant and separate from both my usual self and my surroundings, the glazed eyes in photos from the period attest to this. I recall a moment, looking into a mirror where I could not identify with the image reflected back at me, it felt as though I knew this person well, but that it was not me and I was somehow watching them from elsewhere - a kind of third-person perspective, although the location of that perspective was not clear or separate in any kind of spatiotemporal way.

Reflecting on (Drunk) Altered States of Mind

Reflecting on (drunk) altered states of mind

While I wasn't particularly afraid of this strange experience, I sensed that something was amiss. At the time, it was difficult to objectively compare it to my usual state, and paradoxically, it also felt oddly familiar. Only in hindsight did I realise the peculiarity of the situation.

I sometimes wonder whether it’s possible to truly know a different experiential state when in the midst of another. It seems evident that we can distinguish the difference between experiences, but when living through a given experience it is difficult to distance oneself from it. It’s possible that we can reflect on the experience (a type of metacognition) while living through it, but it seems unlikely we can hold in mind different experiences to compare to the current one, i.e., running a set of concurrent experiences. Our current experience is both unique and unitary, although continually shifting along multiple dimensions.

Consider the experience of being drunk. When sober most of us have an idea of what it is like to be drunk, we certainly have a set of memories (depending on how drunk we were when we formed them!) and a set of social and cultural reference points. We may be able to even imagine certain aspects of being drunk, the looser inhibitions and facilitation of freer social interactions etc. This type of imagination could in theory lead us to feel certain aspects of being drunk. However, can one truly understand what it's like to be drunk while sober, or vice versa? My answer is no because experience differs fundamentally from the knowledge of experience.

A Journey Down a Philosophical Rabbit Hole

For the philosophically inclined, it is useful here to consider Frank Jackson’s Mary’s Red room experiment 9, which is a classic refutation of physicalism (the idea that everything is physical). In Mary’s red room, Mary is a scientific expert on the neurophysiology of vision. She has accumulated a lot of knowledge but has never experienced the colour red (she works in a black and white realm!) She knows the wavelengths and all other physical properties of red and how the human nervous system understands and computes colour. The question is does she learn anything new when she steps outside and sees red for the first time? My answer is yes, although I am not compelled to refute physicalism as a result. Through experience, she has learned about what red is like (it’s qualitative dimensions [Qualia]) and stored knowledge of these dimensions in memory and associative networks. Although she already knew about the physiology of the experience of colour, her experience introduced a new realm of knowledge. This knowledge included what she learned from the physical processes of her body engaging in action in an environment. This realm of experience is not replicable in purely theoretical terms.

I think we can go a step further which will help lead us back to the realm of altered states of mind and my experience of depersonalisation.

I believe that there is a fundamental difference between (1) theoretical knowledge of physical processes and (2) embodied, experiential interactions with the world. Furthermore, I argue that even though Mary's experience of the colour red brings her closer to a fuller understanding of what red is, her knowledge of red from this experience is not equivalent to actually experiencing red.

If Mary were to go out and experience the colour red for the first time, she would undoubtedly gain more knowledge than before she left the room. She may have an easier time imagining red and may even dream in red, but even with this new knowledge, she can only truly understand the qualitative dimensions of red during the experience itself. Her conceptualisations, imagination, and memory of the experience are not equivalent to the experience itself. The knowledge that Mary gains beyond her original theoretical knowledge is a richer set of reference points for understanding what red is, but it is still not the same as experiencing red in the moment.

The Inaccessibility of Altered States of Mind

This idea suggest that we cannot truly know what it is like to be in a certain experiential state outside of that state, e.g., we don’t know the experience of being drunk outside of being drunk. This will depend to some extent on the nature of experience; it is easier for us to imagine being angry and for that experience to begin to come into existence due to the top-down effects of negative thought patterns and associations on our physiology. However, once our memories and reference points of anger have led to an actual experience of anger, then we are experiencing anger.

It may be challenging to recreate certain experiences through memory and imagination, particularly in cases of altered states of mind or neurological conditions. Imagining being drunk may work for some. While expectations can be powerful and the placebo effect is evidence of this, I believe that each experience is unique in terms of its knowledge content and cannot be perfectly replicated. Just as every snowflake is unique, an experience is also unique due to its numerous variables, even if it is similar along some dimensions. Perhaps the only experiences that we may come closer to replicating are the minimal, basic constituent experiences, such as those termed minimal phenomenal experience 10, as they have fewer dimensions to replicate (if any at all).

So, my suggestion within the context of my depersonalisation episode is:

(1) From my experience now, I cannot fully know or introspect the dissociative experience I encountered in the past (unless I make a conscious [not advisable] effort to induce it, where I may be able to recreate a similar (although not precise) experience.)

(2) During the dissociative experience, I could not fully know the experience of not being dissociated. I was in the experience as such.

All in all, no wonder I found it difficult to articulate this situation and why many experiencing altered states of mind struggle to articulate their state (i) to others from when they are within it and (ii) to themselves (or others) from outside of that state.

The implications of this are significant when it comes to understanding another person's experience. It suggests that experiences like dissociation are not only difficult for others to comprehend, but also difficult for ourselves to comprehend retrospectively. Although we may have associations and reference points, as well as language to help us conceptualise the experience, these are merely imitations of the actual experience and cannot fully capture its essence.

Therefore, I find myself in a position of desire to gain more insight into my experiences, even if only temporarily, to be able to remember and recount them. However, this is a futile desire, as certain states are untranslatable into language or other modes of communication. Is there a more effective way to convey altered states of mind?

This is where art comes into play. Through poetic language, art can conjure up metaphors and associations. Other media, such as painting, drawing, dance, song, and sculpture, can also hint at aspects of experience and evoke experiences of their own. Technologies like Virtual Reality (VR) have the potential to bring us closer to replicating experiential states, as they allow for audio-visual, spatial, and embodied experiences. I believe this is where the real progress will be made in understanding experiential states like depersonalisation. As mentioned earlier, experiencing these states involves the physical processes of our bodies engaging in action in an environment. To truly understand and replicate them, we need tools and practices that can speak to all of these elements of experience. It's important to note that this also presents a risk of evoking altered states that could have destabilising implications.

A New Form of AI-Assisted Psychotherapy

Creating an experience machine

So far, I have outlined an experience of transitory depersonalisation, discussed the difficulty in expressing it and other altered states of mind and sketched some means beyond language to get closer to these experiences. In essence, what I’m looking for is a kind of experience machine. Not the hedonistic experience machine outlined by Nozick 11, instead one which would allow a temporary experience of an altered state for the purposes of understanding and communication.

I don’t have an experience machine and without the requisite skill and access to technologies, I am some way off being able to create an audio-visual-spatial-embodied demonstration of depersonalisation (although some are trying!). Even if I could, it would perhaps not be advised. As mentioned above, there are risks to our sense of self associated with the use of multi-modal technologies including VR 12, even without explicitly using them to try and induce altered states of mind.

Having said this, as with all new technologies there is a cost-benefit trade-off and a clear utility in moving closer to some of these experiences for therapeutic purposes (recent example: 13). The possible routes include replicating states (a) simply for the novelty of experiencing different states, (b) to harness their transformative / plasticity-inducing effects, and (c) for increasing access to states for communication, artistic inspiration, introspection or therapeutic work.

For the purposes of this piece, I am interested in how we might use technologies for (c). Framed in this context, I wish to explore whether there are technologies that can be used that allow me to better access a previous altered state so that I can both (i) communicate my transient episode of depersonalisation to others better and (ii) understand it better for the purposes of introspection and integration.

Given that I don’t have access to an experience machine that might help with this and that I think it would be dangerous to use it even if I did, what can I use?

Over the past few years, the technology behind text-to-image AI tools has exploded, opening up a raft of new possibilities. For my purposes, one of these possibilities is the use of such tools to produce imagery of altered states.

An Experiment Going Beyond Words: The Utility of AI Image Generation Tools

I will now attempt to go beyond words to describe my experience of depersonalisation by drawing on the latest (at the time of writing [not for long!]) AI-image generation tools. In this exercise I am fully prepared to fail, but the mission is only to get closer to experience, to go beyond the outline in my first passage that relies on language alone. By doing so, I hope to achieve two things: firstly, to convey the experience to others more effectively, and secondly, to gain a better understanding of the experience myself, which can aid introspection and integration.

Here is an excerpt of my ‘raw’ description of the depersonalisation episode:

“I recall a moment, looking into a mirror where I could not identify with the image reflected back at me, it felt as though I knew this person well, but that it was not me and I was somehow watching them from elsewhere - a kind of third-person perspective, although the location of that perspective was not clear or separate in any kind of spatiotemporal way”

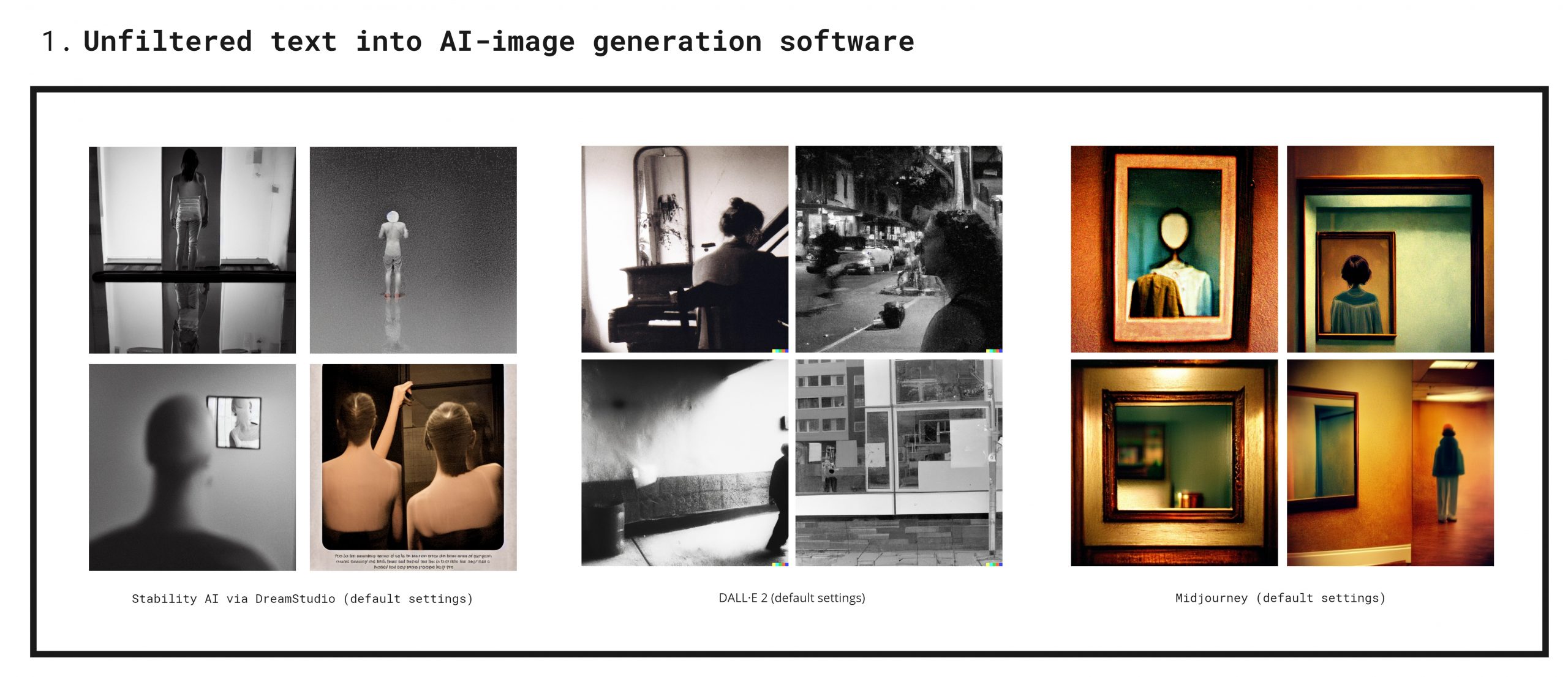

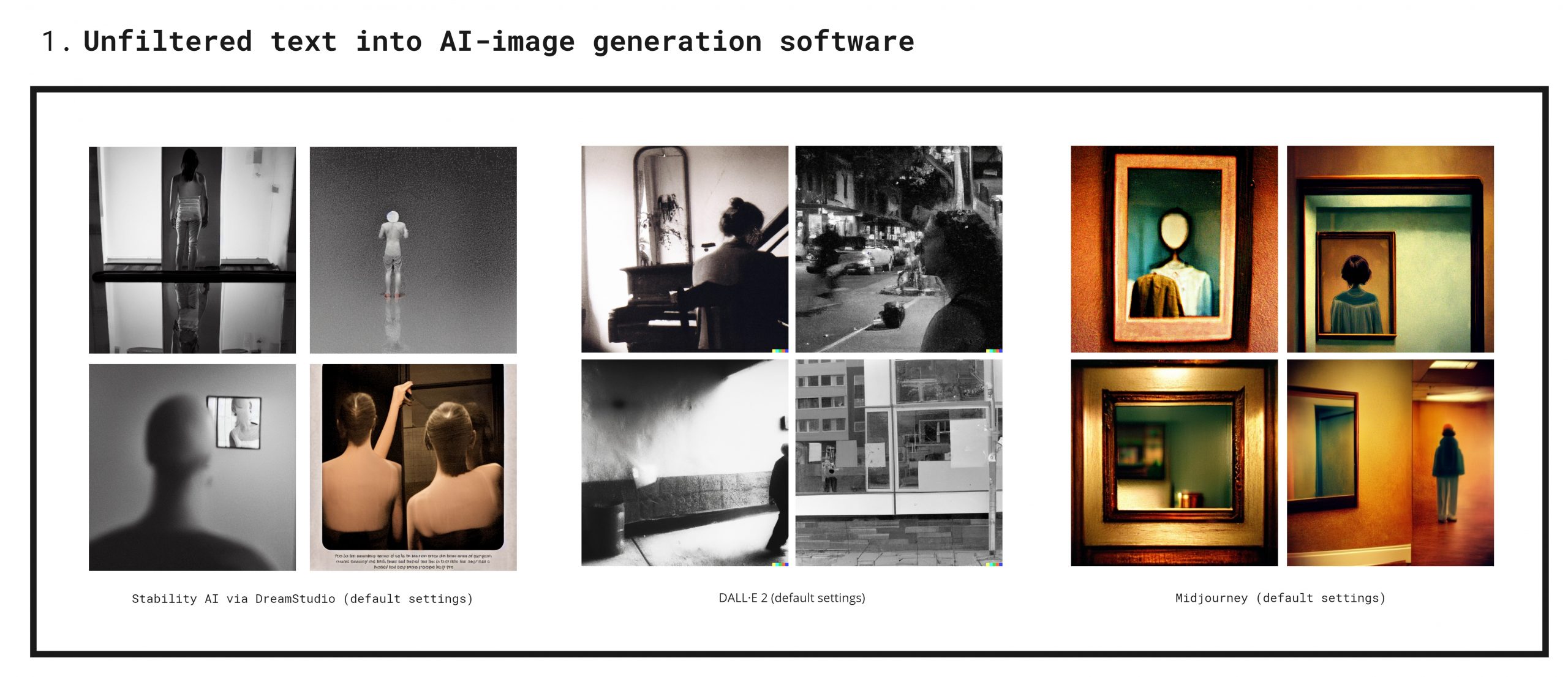

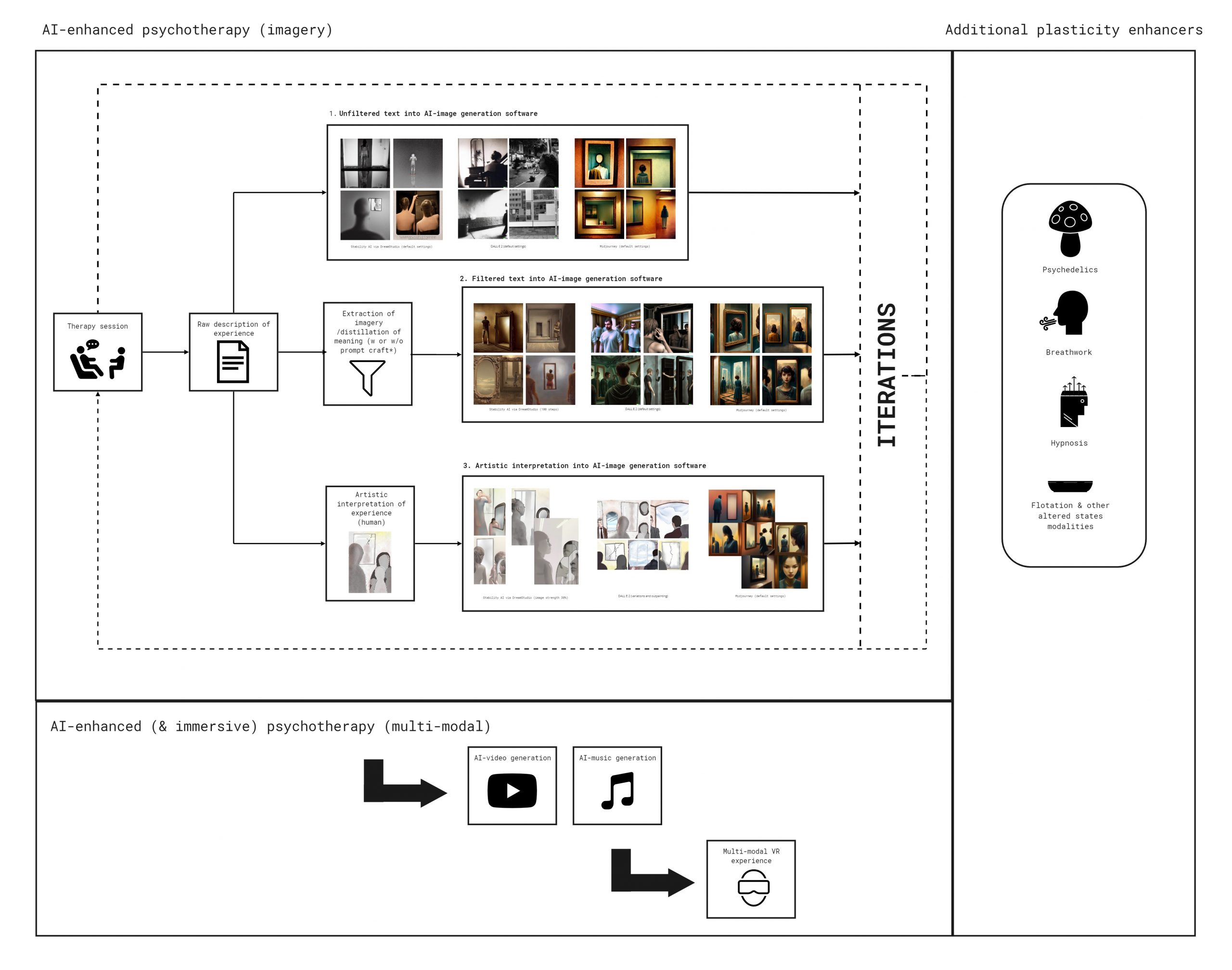

In my first approach, I loaded the raw text prompt into different AI-image generation tools: Stability AI, DALL·E 2 and Midjourney. With each tool, I produced two separate runs of four images. I selected four out of the eight that resonated the most. Each tool has its styles and merits and deals with this kind of ‘raw’ prompting differently. I won’t dig in here, my primary interest is to explore avenues amongst a vast array of possibilities for communicating and integrating this experience.

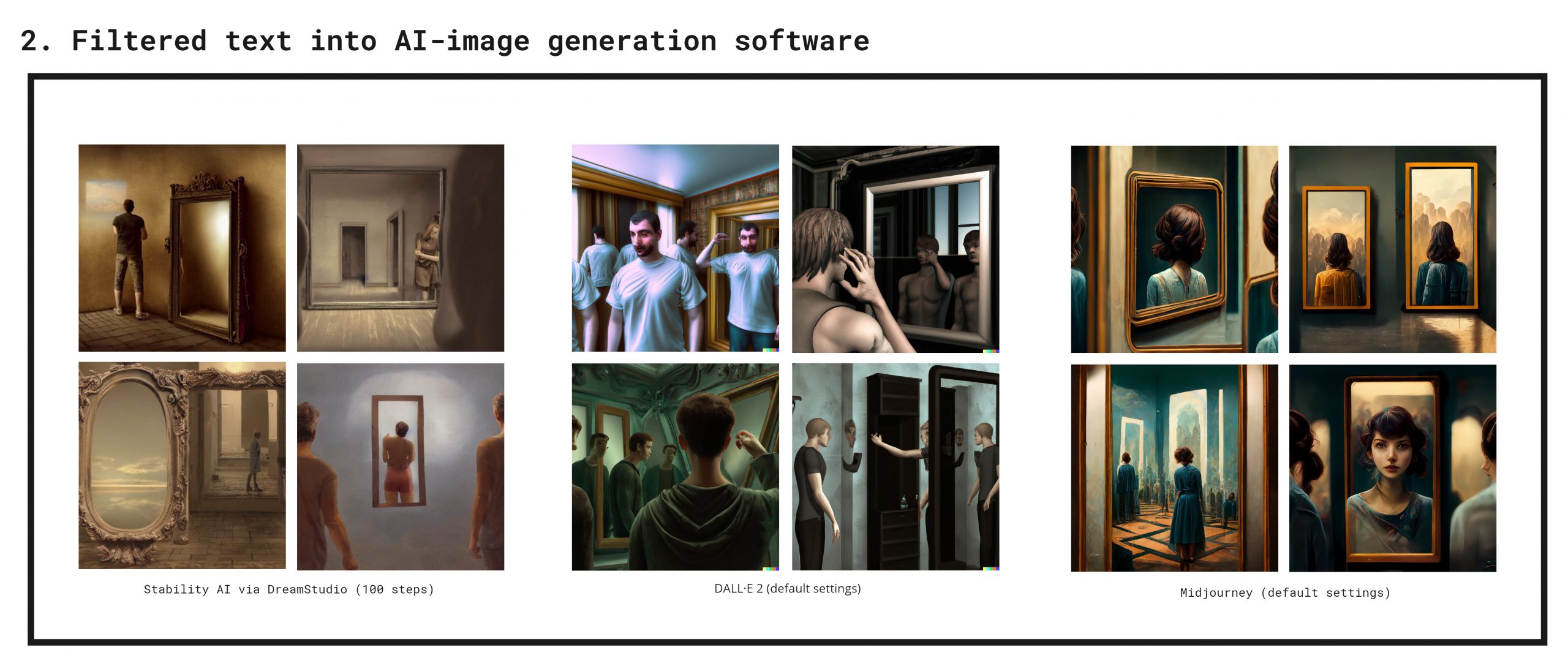

In the second approach, I took the raw text prompt and attempted to extract the core imagery and distil the meaning before entering a shortened prompt into the AI tools. With this I used some tips and tricks, what is called ‘prompting’ or ‘prompt craft’ in the generative art community, aiming at higher quality image outputs. This is what I ended up with:

"A matte painting of someone looking in a mirror, multiple perspectives, confusion, depersonalisation, ultra-detailed"

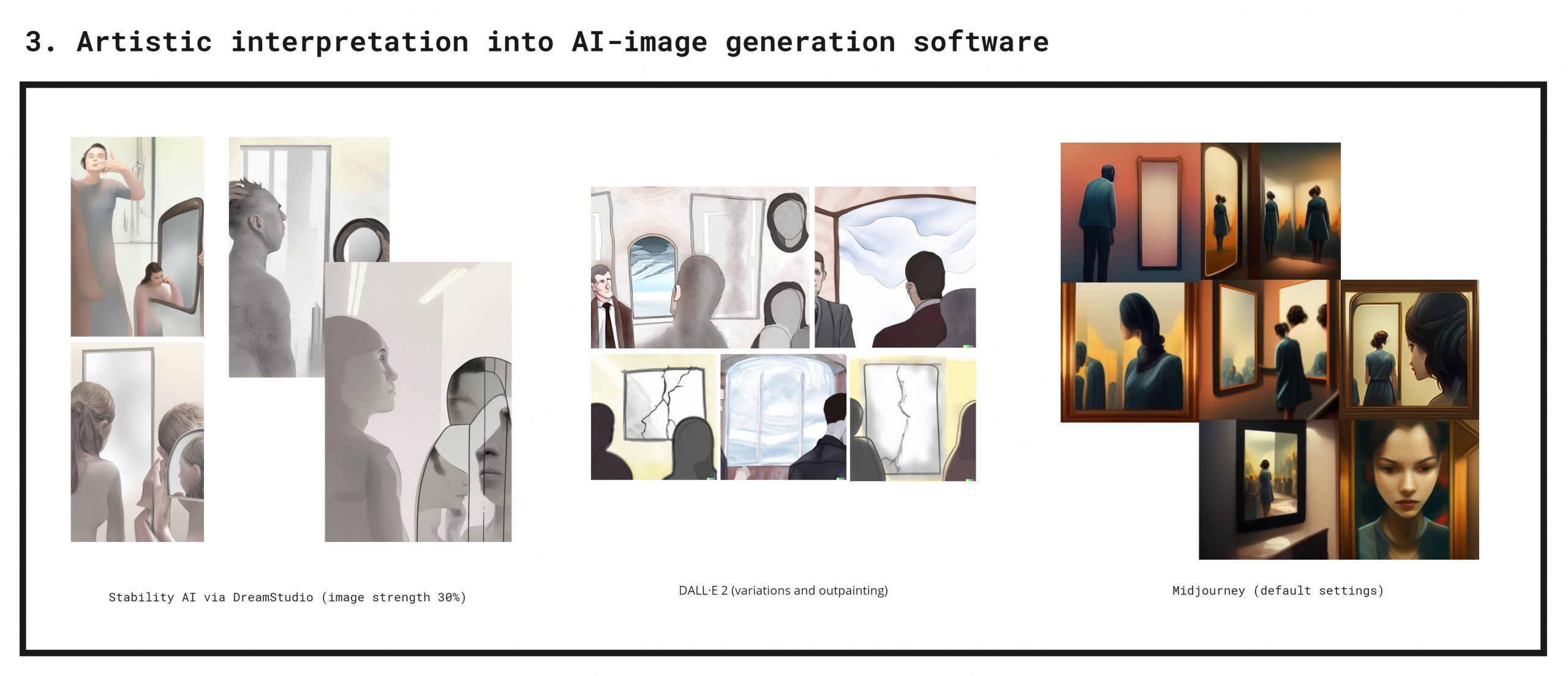

In the final approach, I took a digital image I created and used this as a ‘starting’ or ‘initial’ image in the AI tools. This simply means I loaded the image into the tools and added the prompt from approach two. The image becomes a starting point for the tools to draw from, instead of starting from a random sheet of noise. Here is the initial image:

Reflections on the Experiment

Firstly, I found the process of using AI-image generation tools to depict my experience of depersonalisation both fun and creative. During the second iteration, I condensed my experience and attempted to extract visual elements. As the images were produced, I reflected on how well they resonated with my experience. Some of the images were haunting as they conveyed a feeling tone that was difficult to communicate through words alone - a kind of grey, drab, isolation.

Ultimately, I hope that these images provide another avenue for others to understand the experience I am trying to convey. By combining the text with the images, I can compensate for any shortcomings in my writing skills and communicate with individuals who are more visually oriented or struggle with text, such as people with dyslexia.

Therapeutic Applications: A Modern-Day AI Rorschach Test

As I mentioned earlier, I believe that exploring altered states through multiple modes of expression can provide greater access to the experiences for both individuals and therapists. I have been considering the idea of AI-enhanced psychotherapy for some time now. As part of a research project called 'Living in a Dream,' we conducted a 14-day dream diary study. In April 2022, I ran an exhibit where I used extracts from the dream reports to create AI-generated imagery. This eBook will be launched at the same time as our 2023 exhibit.

The experiment not only intrigued people and created an interesting way for the public to engage with our research but also led to some fascinating conversations. It became clear that the images were not exact replicas of people's dream experiences, but rather representations based on their memories. When some people looked at the imagery from their dreams, they were compelled to associate and enter a dialogue around which aspects were close to their experience, which weren't, and how the images made them feel.

This made me think of the Rorschach test, a psychotherapeutic tool that uses ambiguous images (such as inkblots) to allow patients to free associate. The idea is that their projections and associations may reveal something about their inner world that can be used for therapeutic purposes.

An example of a Rorschach inkblot image, produced using Dalle-2

Could AI-generated images be used in a more sophisticated way for psychotherapy? Instead of using completely ambiguous images like inkblots, therapists could use an AI-image generation tool to create images based on a patient's dreams or other altered states and enter into dialogue with the patient about the content. The images could be refined and discussed further, leaving space for association, and the process could be repeated until a therapeutic goal is met.

I have included this idea, along with the three basic experiments I conducted, in the figure below. Additionally, I have proposed possible extensions using spatial+embodied technologies like VR and AR, as well as plasticity inducers and other altered state modalities. This is a preliminary proposal that will likely take on different forms through experimentation and application.

Closing Words: New Avenues to Explore Altered States of Mind

In this piece, I outlined a first-hand account of a transitory depersonalisation experience likely triggered by a number of stressors. While exploring this experience, I discussed the difficulty of understanding altered states of mind, both in terms of understanding others altered states and one’s own. Responding to this difficulty, I discussed how we might explore ways to go beyond words to describe altered states of mind. I then experimented with various approaches for exploring and integrating these types of experiences using AI image generating tools.

Finally, I introduced the idea of AI-assisted psychotherapy, specifically the use of text-to-image tools to create a modern-day type of Rorschach test. With this, I sketched a theoretical model of how some of this might come together with the use of plasticity inducing altered states modalities and in combination with spatial+emobided technologies of AI + VR. This is a space ripe to explore and fit to change enormously over the coming years as technological advancement open up the potential for new forms of engaging with altered states of mind. Although these opportunities may open up new ways to help people, we should also be cautious of the doors we are opening and the possible dangers behind some of them.

Part III — Who Am I?

By Sarah Coyle

The impact of dissociation on my identity.

Part III: Introduction

The impact of dissociation on my identity.

By Sarah Coyle

Throughout my life I have experienced dissociation, the feeling of being disconnected from both myself and the world around me, in instances both mild and extreme. This has had a profound impact on my sense of self as I do not feel in control of my own experience. My account will explore the ways in which dissociative experiences have caused me to speculate on my own identity and I will discuss various philosophies around this.

Abandoned by My Consciousness

The question of identity has both fascinated and frustrated philosophers for centuries. Can we be defined by our anatomy, our cognition or is there an intangible soul which truly holds the essence of ourselves? Descartes famously said, “I think, therefore I am”. From this, it can be assumed that it is our thoughts which truly define us. The internal monologue through which experience is filtered is the true epitome of who we are. And this does make sense, to an extent. Our thoughts hold our darkest secrets, judgements, desires, and ambitions, surely this is the core of our identity? However, there is an issue with this line of reasoning. We often have no conscious control over thoughts and, particularly when it comes to intrusive thoughts, the concept that our thoughts hold the true secret to who we are can be upsetting. This has led many to suggest that we are instead an awareness of our thoughts, our ‘reflective consciousness’. However, this higher awareness, known as metacognition, is what is under threat when I experience dissociation. I often feel like I lose the mediator between my thoughts and experience which can cause me to question my sense of identity.

In my experience, when I lose awareness of my cognition, it feels like I lose the essence of who I am, my core identity. Interacting with the outside world becomes fragmented and disjointed and it is as if I am watching my surroundings on a screen, rather than perceiving them in the moment. It is almost like zoning out with the inability to zone back in, no matter how much effort I put into doing so. This loss of metacognition and the resulting disconnect between myself and my surroundings has left me uncertain of my own sense of identity. I have long since come to terms with the concept that I am not my thoughts; one mean or judgmental thought does not automatically define my character. I have also learnt to identify intrusive thoughts and not let them infringe on my sense of identity. However, if I am not my thoughts and I regularly lose the awareness of my thoughts then what is left?

The Self and Buddhism

So far, I have only considered the self as a unified entity, a concept prominent in western philosophy. However, my experiences with dissociation have caused me to lose my sense of self and I have therefore found it more useful to consider the Buddhist perception of the self. The doctrine of no-self, particularly prevalent in the Mahayana school, is one of the most important teachings in Buddhism. Instead of considering the self as a unified entity, we can instead consider ourselves an aggregate of our form, feelings, perception and consciousness. These different aspects of the self are all impermeant and constantly changing and reforming, therefore, there is no static conceptualisation of the self. This is remarkably similar to David Hume’s philosophy of the self in which he denied the concept of a unified self and described man as a “bundle or collection of different perceptions”. Considering my identity this way, as simply a collection of my experience and perceptions, has been an invaluable contrast to the threat dissociation held over my sense of self. No matter how far away or disconnected I feel, I can hold on to my perceptions and experience to cement my identity.

Defining the Undefinable?

Often, when trying to explain dissociation to friends and family I am at a loss for words. The experience is so intangible that, by its very nature it is impossible to define. I often resort to metaphors to enable people to understand the experience and, while not perfect, this is the best way to help people understand. I often liken the experience to static; everything feels somewhat fuzzy and dampened. It is as if someone has wrapped my mind in the flimsy plastic that new electronics come in. I am not completely cut off from the outside world however there is a distinct disconnect. It makes it difficult to find meaning, both in interactions with others and in my own thoughts. For example, I may be aware that I am hungry, but I don’t always feel ownership over my hunger. It is important to note that dissociative episodes vary wildly in nature from person to person and this account is not representative of everyone’s experience. However, I believe that a universal feature of dissociative experience is the difficulty in putting it into words.

I was talking about dissociation to a friend of mine and she told me that she has very similar, but slightly more extreme experiences. She did not realise that there was a name for these episodes that she was having and thought that she would be laughed at if she tried to talk to anyone about it. This highlights how a lack of awareness around dissociation can prevent people from sharing their experiences, further contributing to a general absence of understanding. Dissociation has been found to be the third most common mental health symptom (after low mood and anxiety) however there is very little understanding of it. It is thought that up to 75% of people experience dissociation at least once in their lifetime, however many have no awareness of it and therefore would not be able to identify their experience. I believe that this is due to the difficulty that people have in describing it, which can prevent people from getting the help they need. It is clear, therefore, that dissociation needs to be more present in discussions regarding mental health.

My Experience

I most often experience dissociation when I am experiencing heightened anxiety or stress. It feels counterintuitive that my mind copes with stress by putting me through something that is highly stressful, but when has my mind done anything that makes sense? During A levels, I had these experiences up to a dozen times a day. They would be pre-empted by a strong sense of unease, the feeling that something wasn’t right, that I needed to leave. They would also often be accompanied by overheating which added to the anxiety that these experiences caused me. Not knowing what I was going through, I defined these episodes as anxiety attacks. When asked, I described the sensation as “feeling faraway” to which I was met with confused stares. As I got older these episodes ceased, however, I still experienced dissociation, albeit in a different form.

I have been prone to fainting my whole life and, in the moments before I lose consciousness, I experience a much more extreme form of dissociation. I fell as if I completely leave my body; I have physical control over it, but my mind is somewhere else entirely. It is like falling backwards into my own consciousness, and then there is normally a minute or so where I feel as if I exist slightly behind my body. This is probably similar in nature to an out-of-body experience (although this is something that I have never experienced) which although often evoking spiritual connotations, is thought to be an extreme form of dissociation.

Multiple Centres of Consciousness

My experiences of a different form of consciousness during these dissociative episodes have led to me to re-evaluate the very nature of my own conscious experience. My previous conception of consciousness was of it existing as an all-or-nothing concept; there is either consciousness or there is not. However, I am now more inclined to adopt a different viewpoint.

One approach is to view consciousness as existing on a continuum, this makes intuitive sense as we experience different states of consciousness as part of everyday life. Dreaming can be viewed as an alternate state of consciousness, as can mind wandering. It could be that dissociation is an involuntary slip into a different form of consciousness that some people are more susceptible to than others. It is also possible that there are individual differences in one’s default level of consciousness. It has often been proposed that people may perceive colours differently, however, we have no way of knowing what they objectively look like. It is possible that this is also the case with consciousness. Our own experience is all that we have ever known and therefore we cannot be aware of individual differences in the ways that others experience their surroundings.

An alternative theory is that consciousness is not a unified concept, and we possess several centres of consciousness. This is a concept touched on by Jung (1935) when he stated that "The so-called unity of consciousness is an illusion... we like to think that we are one but we are not”. An exploration into this theory was inspired by split-brain patients; these are individuals who have undergone surgery which cuts the corpus callosum, the bundle of nerves which divides the two hemispheres of the brain (a treatment for those with sever epilepsy). These patients, therefore, have no communication between the two hemispheres. Some patients experience “alien hand syndrome” which is a neurological disorder in which the patients hands often take on a mind of their own. Some patients described their hand unbuttoning their clothes or knocking items off a table. This led some researchers to suggest that patients had split consciousness and that there is a centre of consciousness in each hemisphere of the brain. This implies that it is possible to divide one’s consciousness into multiple centres. If this can happen as a result of surgery, it is logical to assume it could also happen in other circumstances, perhaps as a result of trauma.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a severe form of dissociation and involves feeling the presence of other identities, often each with their own voices, personalities, and mannerisms. DID is thought to be a way of coping with sustained childhood trauma and is a very normal defence mechanism. One theory as to why this phenomenon can occur is that, when physical escape is impossible, mental escape is the only possible solution. The experience is so emotionally overwhelming that the individual cannot cope and blood flow from the front of the brain is redirected to the back part of the brain with can affect their perception of reality. However, the dual conscious theories surrounding split brain patients have led me to wonder whether an alternative theory is plausible. It could be that, in the same way that surgery could cause consciousness to divide into two separate entities, extreme psychological trauma causes one’s consciousness to spontaneously split into several entities all competing for control (please note that this is entirely my own speculation and should not in any way be taken as fact). This would explain why sufferers of DID experience the presence of other identities, it is simply the other centres of consciousness taking control. This challenges the concept of a unity of consciousness and suggests that consciousness is more fluid and variable in nature and those who experience dissociation are experiencing a different form of consciousness.

Conclusion

Dissociative experiences have accompanied me my whole life and have caused me to question all aspects of my identity. However, I have found that letting go of a strict, unified concept of the self has helped me to more understand my own consciousness.

Part IV — Dreaming Your Reality

By Joe Perkins

My experience of depersonalisation and derealisation disorder.

Part IV: Introduction

**My experience of depersonalisation and derealisation disorder.

**By Joe Perkins

I’ve experienced Depersonalisation and Derealisation Disorder chronically for over 15 years. There hasn’t been a single moment of ‘normality’ during my whole adult life, and the symptoms have intensified as the years have gone on – something which no medical intervention has been able to slow, let alone reverse. Coming to terms with how this holds me back and has impacted the dreams I once had for myself continues to be a distressing and depressing journey. But I’m not alone: 1% of the general adult population feels permanently estranged from their ‘sense of self’ with many more encountering the sensations episodically. Though despite this prevalence, general awareness of the condition remains low – psychologists and psychiatrists frequently resort to Googling the symptoms during appointments like the rest of us do.

If talking about living with this illness reaches just one person struggling to identify their experiences, or encourages just one clinician to take the condition as a point of interest, that makes the difficulties of opening up about how my life has become feel worthwhile.

Playground Politics

Every school has those one-in-a-hundred kids who are just a bit different – and for those of us who become acutely aware we’ve been shoehorned into that role from a young age, it tends to become a part of our personality we struggle to shrug off in later life. A bit like an actor becoming over-synonymous with a particular character: every time Richard Wilson pops up in a serious period drama, you’ll know whose quotes my brain is inappropriately spewing out.

Depersonalisation and Derealisation Disorder (from hereon in DDD, primarily to save ink) has been a defining theme of my life since 2008. I was 18, studying for my A-Levels, and – having been cemented as the oddball a decade previously – was still enduring painful bullying daily. Home life was somewhat fractious and overwhelming; ‘social connection’ was an alien concept; and whilst the Tories-In-Training I was lumped in with at school were all paving the way for their illustrious future careers, I was simply trying to survive each day and get to bed without cracking. I was a loner. I felt trapped, stressed, and constantly under threat. So, in terms of the protective reflex of the mind concept that underpins current psychological theories behind DDD, I was hitting bullseyes for risk factors.

The one solace I had in my life was music. My grandad played the piano with me from an early age, but discovering the electric guitar as a teen was when it all became more therapeutic. Without wanting to sound too flowery: music became my safe, protective little world. Whenever I was listening to an album or fumbling my way through metal riffs, nothing else mattered. Because at those times, the bullies had no power – I was louder than them.

It might have been a coping strategy more than a hobby, but it was a positive one. It was all I really had to keep me going anyway.

Enter Depersonalisation

Like so many people, when my symptoms began I had absolutely no idea what was happening to me. At first, I just thought I was tired and burned out. But when I couldn’t sleep them off – and they kept intensifying – I knew something wasn’t right. I took a year out after school and worked selling CDs (remember those?) in a shopping mall, but everything was feeling progressively more dreamlike. I’d stand behind the tills, looking down the racks of discs and feel like I wasn’t actually there. The shop was noisy and busy, but it also felt like I hadn’t yet woken up and I wasn’t taking anything in. There were elements of my lived experiences that were changing and becoming distorted. I knew I was a real person, and I knew my surroundings were real – but there was a growing sense that my daily life was becoming more like a simulation.

A common metaphor you hear for DDD is, ‘I feel like I’m a character in a movie’ – and despite Jackass 3D being about as high-brow as I’ve ever ventured into the world of film, I do think this is pretty accurate. When you’re in a cinema and immersed in a movie, you feel – in many ways – like what you’re seeing is actually happening. You’re invested in the storyline. You’re wanting the good guys to mash the alien. You feel the tension. You jump in your seat when some churlish demon hoofs the door down. You might end up crying or laughing. The film does become a sort-of reality that you experience yourself.

But in the back of your mind, you understand it isn’t your reality. You’re responding to a story. The people you’re watching smack each other about aren’t really furious – they’re reading a script, and probably for the tenth time since their lunch break. Tears aren’t genuine tears. Visuals have been carefully constructed. It’s all fake. And whilst you do react in many of the same primeval ways as you might one of your own situations, there’s a subconscious separation between that reality and your reality. The events aren’t happening to you. You’ve chosen to place yourself in a controlled, imitated situation to temporarily experience theoretical scenarios from afar, before removing yourself once the novelty wears off – like riding a themed rollercoaster at Disneyland.

[Insert clichéd comment about said rollercoaster never stopping for some people here…]

In so many ways, the early years of experiencing milder symptoms than I do presently were more distressing than today, simply because it was all a great unknown. Something was taking over my mind and no bugger had a clue what it was. My emotions were evaporating. I was becoming a zombie. Therapy, pills, scans, diets, exercise, blood tests – nothing could stop me from falling into an even deeper sleep.

The Best Show I Never Went To

Of all the bands that kept me distracted from the hard realities of being an outsider, Lowestoft rockers The Darkness drew my attention the most. I still have their posters on my bedroom wall to this day. The music was great, but they didn’t take themselves too seriously – there was good humour underpinning it all. Heavy guitar riffs were somehow more engaging when the accompanying lyrics were all about giant mythical dogs, or masturbation.

Their music and gigs gave this terrified introvert much needed catharsis and a vague sense of communal belonging. I once travelled the country to see the same show three times in a week. The outside world vanished once the house lights went down and ABBA’s Arrival began to blare out as they took to the stage. It still does, come to think of it.

But there was one show that always felt a little different to look back on. I could see the venue in my mind; I remembered the queue to get in being long and cold; I could tell you which songs they played; and the guitar nerd in me could even recollect Dan Hawkins started out playing his Gretsch, which was slightly unusual for a Les Paul man.

But what always evaded me was being able to pinpoint where and when this gig had happened. Memories of the others were all equally as vivid, but they came with the cognitive metadata that allowed me to attach their location and rough date. This one was different. It was like the memory had become corrupted and that data was scrambled.

For months – years, even – I wracked my brain. Was I going crazy? I could remember the complexities – so why not the very basics? I felt like I was losing my mind. Frantically trying to answer that question ate away at me. I’d lie awake at night terrified I was losing the plot. It must have been that night at The Astoria in London, right?

But I slowly began to figure it out. I had dreamt the entire thing.

Yes, my subconscious had ample material to cobble together something that was akin to previous genuine experiences – the shows were all different, but not that different. But it felt so damn real, and you don’t typically question the actual existence of your real experiences. It never once occurred to me that I might have imagined standing in the crowd at that show. Realising that I had, after going so long believing it to have been a genuine part of my life, was such a difficult realisation to come to terms with. Is this what my life was becoming? What next? I tell somebody about dreaming being on another planet and they’ve already seen it on the news?

Now, I’m asking these sorts of questions every single day. The boundaries are so blurred that I often genuinely don’t know what’s been a dream and what hasn’t. Recent research has proven this to be a measurable phenomenon; but that doesn’t make it any easier.

Do You Wake Up Next to Your Partner?

I’ve been in a relationship with Sophie for over six years. In many ways we’re perfectly suited to each other, and she’s very understanding when I try to explain my problems, even though it’s impossible to really ‘get’ them if you’ve not been here yourself. It takes a special sort of person to hear their partner say, ‘I’m not able to feel love for you,’ and understand that to be a painful side-effect of a psychological problem, rather than assume it’s some Jack the Lad taking them for a ride.

But things aren’t plain sailing – and having the limitations DDD imposes on me negatively impact somebody else is one of the hardest things to live with. Though, for a condition that feels so overwhelmingly isolating, the comfort of somebody being here with me to hold my hand through the struggles is certainly worth the pain it can sometimes bring to us both – at least from my perspective. I do wish I was able to be more supportive for her; make her happier; be more enthusiastic about things we do together; and – when I’m feeling especially horrendous – be a less irritable, frustrated, moany bastard. I’m far from a perfect boyfriend. But even if it's ‘only’ on a logical level rather than a felt-emotional one, she is my soul mate.

This makes it even more difficult when I wake up in the morning, look over at her, and I don’t know who she is. I see her face and don’t recognise her – sometimes, she doesn’t even feel like a human being. There’s this thing looking back at me. Her voice sounds like a stranger’s. Her words don’t register with me on anything below surface level. If you were to ask me, I could instantly tell you that she’s Sophie, and she’s my partner. But those are just words. My internal perception of the whole situation is much more harrowing.

In so many ways, I haven’t woken up at all.

But another little-discussed effect of DDD is how it can largely remove your sense of ‘consequences’ – because when you live life asleep, there’s surely only ramifications of what you do and say once you wake up, right? It’s like being back in the cinema watching the film – you feel like it’s somebody else’s story that you’re casually dipping in and out of.

I’ve always promised Sophie 100% honesty – especially when it comes to my condition, and about our relationship. But sometimes, I wish I was able to exercise more discretion. I think I can be more-than-overly frank. I’d rather she knows the truth about how I’m feeling (or not feeling) regardless of how clumsy it might come across to somebody who hasn’t experienced DDD. Sometimes, a small corner of my mind is screaming, ‘You can’t actually say that!’ as the words are already leaving my lips. I tell her precisely what I’m thinking, which isn’t always pretty. And, despite believing that honesty is usually the best policy, it makes me feel bad that I’m so detached from my life that I’m not able to actively consider the ramifications of being as brutally to-the-point as I can be.

But that’s what happens when your whole existence feels like a lucid dream. If you thought your life had an ‘Undo’ button; or knew that if you upset somebody, you could make the memories disappear and try wording it differently; would you sometimes take more liberties with what you say? I think DDD creates that same headspace.

Nightmares Are Still Dreams

Everybody reacts to mental health discussion differently. Contrary to the stereotypes though, I’ve never really found there to be much of an age-divide in attitudes – unless you’re the Daily Express, it seems far more individual than that. A family member in their nineties sent me a letter saying how much they learned from my book and how valuable they thought it was to have written it; yet I’ve had people born in this millennium be vile. Boomers aren’t the exclusive problem.

But there’s one view on DDD specifically that has always baffled me – and I’ve had it said to me surprisingly often. Maybe I’m just a closed-minded product of a backwards Western society who can’t see the world beyond their next shiny new purchase. But whenever I hear it, I couldn’t really disagree with the perspective any more strongly.

‘You have achieved enlightenment! Please teach me how to feel the same – God has chosen you!’

God has not chosen me. At least, I don’t think so. If they have, they’ve got a screwed-up sense of humour. If floating through life, feeling like you’ve been stuffed with tranquilisers and struggling to get out of bed in a morning whilst having your partner feel like a space alien is thought of as an attractive destination, I want to go home, hide the car keys and deadlock the front door. Forever.

I think one key factor that is missed in this idealised worship of the condition is the transitory nature of such similar experiences that people work hard to access (especially as those tend to pivot around ideas of ‘connection’ – particularly to nature – which is the exact opposite to how DDD feels anyway). I can absolutely see how feeling spaced out like this temporarily could be useful, fun, or even pleasant. Hell, people fill themselves with recreational drugs to feel like this. And let’s not forget that dissociation is a ‘correct’ psychological response to many situations – it can save your life and help you to endure hardships. It’s bloody useful sometimes.

But the beauty there is that the sensations don’t last. At some point, you drift down and back into reality. The most pleasurable and revered things in life are generally only regarded as such because they don’t come around very often. You can have too much of a good thing. I love Formula 1, but if there was a race every day I wouldn’t watch it – ‘only’ 90 minutes a fortnight keeps it a desirable commodity.

The way I would best describe it is this: I love a drink. If you want to meet me, I will suggest the pub. A lot of people are the same. But imagine if the first time you ever enjoy a pint, the tipsy feeling never goes away. If you have another pint a few months later, you’ve then had two pints, and that feeling doesn’t go away. You never sober up – and the squiffiness is cumulative. If this were the case, ask to meet me and I would probably suggest a coffee instead. The effects being irreversible would somewhat take away the appeal of a messy night out, wouldn’t it?

Describing DDD to people as feeling ‘like being drunk all the time’ is a helpful metaphor – and when the predictable response to that is usually, ‘That sounds brilliant!’, I do understand it comes from a sense of awkwardness around them not knowing the best thing to say. I get it. But I think the same is true of the enlightenment folks. I’m not sure they’ve really thought through the full ramifications of what they’re putting on the pedestal. The grass might always seem greener, but if they go to find out for sure and can’t then come back, it might dawn on them they’re spending the rest of their life sat alone in a field.

Reframing the Depths

As somebody who has their personal and professional life significantly controlled by this condition, surplus income is something of a fantasy – so when it comes to healthcare, I’m limited to what I can access on the NHS. Nowadays, they’ve largely washed their hands of me – every time I approach the local mental health team begging for help I get discharged as soon they remember they’ve never heard of my diagnosis. A reaction conducive to feeling hopeful about your future it is not.

Online, whenever I’m unable to gift somebody ‘the cure’, or I mention that after 15 years of trying to get better I’m actually feeling a hell of a lot worse, I’m frequently accused of scaremongering. “I truly hate you. You never have anything good to say about this condition,” one person felt they needed to tell me. I’d love to know what they were wanting me to say. Voicing my genuine thoughts would have probably gotten me banned from YouTube.

But amongst the hate people throw at me – which feels very overwhelming at times, and makes me question whether I should follow their advice and disappear back into the hole from whence I crawled – there’s also a lot of positivity. Especially since I’ve been a part of the charity Unreal, I’ve felt a growing sense that advancing our collective understanding of this condition is only ever going to happen if it’s led by those of us living with it.

In every peer support session when somebody gets emotional because they’ve met others who validate their experience after years in the wilderness; every time somebody says we’ve been instrumental in them finally getting a diagnosis and treatment; every time I’m asked to join a steering group for a new DDD study by a researcher who really believes in our cause and wants to help; every time somebody takes the time to email me and say that my book really meant something to them, or that my short film finally gave a search term for their symptoms…that is my silver lining. It’s far from the one my YouTube commenter would want to hear. But for a community in which there is so much quiet suffering, so much frustration, and often so little sense of hope…we’re a bloody strong bunch.

Speaking about the raw difficulties of living with this condition can feel uncomfortable. But thinking that doing so might reach somebody who has been feeling as alone and frightened as I did for so many years…they are why I continue to do this. This is how I get through this condition nowadays. I’d be lying if I said I was hopeful of ever feeling any better myself – but if discussing the trials and tribulations frankly can help others feel like somebody is with them holding their hand, that’s about as positively as I can possibly frame this nightmare.

And anyway, talking about it isn’t that uncomfortable. It’s not like it has consequences.

Part V — Here, but Not Really

By Gwendalyn Webb

A reflection on my journey living and coping with Depersonalisation Derealisation Disorder.

Part V: Introduction

A reflection on my journey living and coping with Depersonalisation Derealisation Disorder.

By Gwendalyn Webb

I am neither a writer, clinician, nor philosopher. I do not pretend to understand the complex inner workings of the mind nor the world around me. I am in the modest percentage of those living with Depersonalisation Derealisation Disorder and in the following chapters I discuss my personal journey living with the condition, in the hopes that it might bring some comfort to another in the same boat.

Content warning: This piece talks about suicidal ideation, dissociation, derealisation, depersonalisation, identity, isolation, grief, trauma.

I Think, Therefore Who Am I?

I am not sure that I know what a soul is, and if I believed in its existence, where it would live in the body. If not a soul, then whatever it is that makes up the internal sense of self; what we are; who we are seems to have been lost for me (if indeed, I ever had it in the first place). If there was a single moment in which it occurred, I cannot remember the precise point in time. All I know and can recall is that at some point, years ago, whoever “I” am splintered away from my person. I think it was gradual, like a stress fracture, cracking further with every motion. Surely, bit by bit, I broke away from me until one day I was no longer here.

Now I no longer wake up and experience the day. Instead, I rise in the morning and put on my body. I slip into my skin and organs and bones, and I rattle around inside, watching my flesh suit go about it’s business, deceiving all those around with me with normality. I seamlessly transition from sleep to daytime to maladaptive fantasies in my mind unconsciously; muscle memory changing gear autonomously from dream to reality. One steady stream of unconsciousness; the difference between asleep and awake barely perceptible.

To communicate this experience would read like a woeful ballad; colours muted to grey, taste burned to ash, pain muffled to a stifled yelp and happiness no more than a theory. Pretty dramatic for the grounded reader.

But my flesh suit appears jovial since it is smiling today, so I “must be feeling much better”. My suit is a friendly imposter, my armour for the world. It ferries me around taking the liberty of laughing on my behalf at things that I can only assume I find amusing. I can cower in the recesses of my mind barely aware of where my suit has taken me, and who it is talking to.